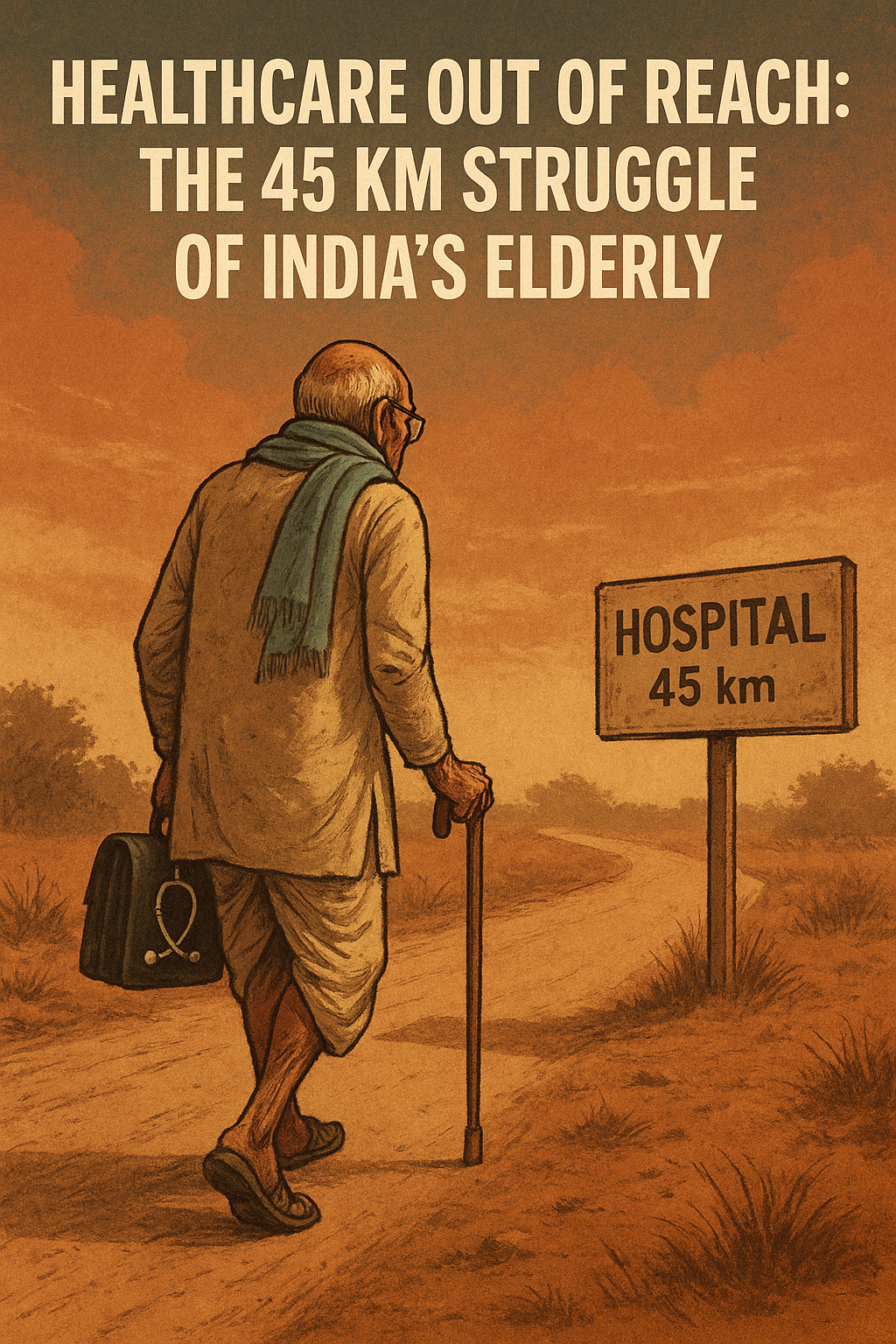

In a country where family values and respect for elders are integral to the cultural fabric, it is disheartening to learn that a significant segment of our senior citizens is forced to travel an average of 45 kilometers to access basic healthcare. According to a recent report jointly conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), elderly citizens in India, especially those in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, face serious hurdles in availing outpatient department (OPD) services. This situation is particularly grim given India’s rapidly aging population and the rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among the elderly.

A Grim Reality for the Aging Population

As per the study, which surveyed over 32,000 elderly individuals across the country, elderly patients often need to cover an average distance of 45 kilometers to get themselves admitted to hospitals. Even to avail OPD services, many of them need to travel around 15 kilometers—a distance that may seem negligible to the young, but can be a major challenge for the aged, particularly those with mobility issues or chronic illnesses.

This issue is not merely about distance—it’s a reflection of systemic healthcare inequities and infrastructure gaps that continue to plague rural and semi-urban India. The findings from this study are alarming and bring to light the silent suffering of a vulnerable group that deserves our utmost attention and respect.

Urban vs. Rural Divide

While cities may offer healthcare facilities within a relatively accessible range, the contrast in rural areas is stark. The study, which used data from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) from 2017-2018, highlighted that in urban areas, around 73% of elderly individuals were able to access OPD services within a 5-kilometer radius. In comparison, only 41% of the elderly living in rural areas had similar access.

This disparity is not just a reflection of geography, but of governance, planning, and prioritization. Rural areas, where a large portion of India’s elderly population resides, are often deprived of adequate medical personnel, diagnostic facilities, and transportation support. For many elderly people living in these regions, healthcare becomes a distant dream—both literally and figuratively.

The Mountain States: A Steeper Challenge

The challenges are even more severe in hilly states like Sikkim and Himachal Pradesh. The study found that in these regions, 17% and 5% of elderly individuals, respectively, had to travel over 10 kilometers just to access basic OPD services. Mountain terrain, lack of road infrastructure, and unpredictable weather conditions only add to the difficulties.

In Mizoram and Nagaland, despite the state’s efforts, the availability of nearby healthcare services remains a major concern. People are often forced to undertake long, arduous journeys over difficult terrain just to consult a doctor—something that should ideally be a basic right, not a privilege.

A Silver Lining: Lessons from the North-East

Not all news is grim. States like Tripura, Manipur, and Kerala have shown how things can be done right. The report mentions that in these states, over 80% of the elderly population can access OPD services within a 5-kilometer range. Kerala, a consistent leader in health indices, once again proves that proactive governance, investment in public health, and decentralization of healthcare can yield commendable results.

In these states, the focus has been on strengthening primary healthcare centers, deploying mobile clinics, and ensuring better outreach through ASHA workers and local health volunteers. These models offer valuable lessons for other states grappling with similar challenges.

Underlying Issues Behind the Numbers

At the core of the issue lies a complex interplay of multiple factors:

- Inadequate Primary Healthcare Centers (PHCs): Many PHCs in rural areas are understaffed and ill-equipped. Where facilities exist, there’s often a shortage of trained medical professionals or essential medicines.

- Poor Transportation Infrastructure: Many elderly patients depend on public transport or their families for travel. In places with poor roads or limited transport facilities, even a 5-kilometer distance can be a significant barrier.

- Economic Constraints: Many elderly individuals live on minimal pensions or are financially dependent on others. The costs involved in traveling long distances for routine check-ups or treatments act as a deterrent.

- Lack of Geriatric Care Facilities: Most hospitals and PHCs lack specialized services tailored to the unique health needs of the elderly, such as geriatric clinics, physiotherapy, or chronic disease management programs.

What Needs to Be Done?

The findings from this study should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers, public health officials, and civil society. Some immediate and long-term steps can help address this crisis:

- Strengthen Rural Healthcare Infrastructure: Investment in PHCs and community health centers, especially in remote and rural areas, is the need of the hour. Facilities must be equipped with trained personnel, diagnostic tools, and essential medicines.

- Deploy Mobile Health Units: Mobile clinics can be a game-changer for remote and hilly areas. These units can bring basic medical services to the doorsteps of the elderly.

- Promote Geriatric Healthcare Training: Medical professionals must be trained in geriatric care to better cater to the complex needs of the aging population.

- Improve Transport Access for the Elderly: Subsidized or free transportation for medical visits, especially for those above 60 years of age, can ease the burden significantly.

- Encourage Community-Based Care Models: Involving local volunteers, NGOs, and ASHA workers in health monitoring, medicine delivery, and check-ups can significantly improve accessibility.

- Digital Health and Telemedicine: Especially in remote areas, digital consultations and remote monitoring can bridge the gap between doctors and elderly patients, reducing the need for physical travel.

Conclusion

India stands at a crossroads. With the population aging rapidly, healthcare access for the elderly must become a priority—not just in words but in actionable policy and implementation. A society is often judged by how it treats its weakest and most vulnerable members. For our elderly, who have contributed a lifetime of work, wisdom, and resilience, the least we can offer is accessible and compassionate healthcare. The 45 kilometers they walk today must be replaced by a healthcare system that walks towards them.